Hours after escaping the Columbine High School shooting, 14-year-old Missy Mendo was sleeping between her parents, wearing the same shoes she had worn to escape her math class. She wanted to be ready to escape.

Twenty-five years later, Mendo became a mother herself, and the trauma of that horrific day still lingers.

She realized this in 2017 when 60 people were shot to death at a country music festival in Las Vegas, a city she visited frequently while working in the casino industry. In 2022, 19 students and 2 teachers were shot and killed in Uvalde, Texas.

Mendo was filling out her daughter’s kindergarten application when news of the elementary school shooting broke. She read a few lines from a news report about Uvalde, then hung her head and cried.

“It felt like nothing had changed,” she recalls.

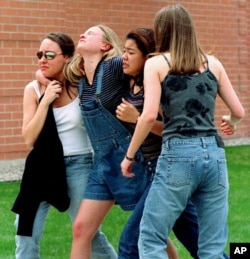

Twenty-five years after the two Columbine gunmen killed 12 classmates and a teacher in suburban Denver (the attack was broadcast on live television and ushered in the modern era of school shootings), the trauma of that day Shadows continued to loom over Mendo and others present.

It takes years for some people to consider themselves Columbine survivors because they were not physically harmed. Yet things like fireworks can still trigger disturbing memories. In the years before mental health issues become more widely recognized, the aftershocks often go unacknowledged, causing some survivors to lose sleep, drop out of school, or become disconnected from spouses or family members.

Survivors and other members of the community plan to attend a candlelight vigil on the steps of the state Capitol Friday night, the eve of the anniversary of the shooting.

April is particularly difficult for Mendo, 39, whose “brain turns to mashed potatoes every year.” She went to the dentist early, forgot her keys, and forgot to close the refrigerator door.

She relied on therapy and understanding of the growing community of shooting survivors she met through the Rebel Project, a support group founded by other Columbine survivors after the 2012 incident at a movie theater in a suburb near Aurora In the shooting, a gunman killed 12 people. . After her child’s first birthday, Mendo began seeing a therapist at the urging of other survivor moms.

Mendo, a single parent, said after her debacle over Uvalde, she talked with her mother, went for a walk to get some fresh air and then completed her daughter’s pre-kindergarten application.

“Am I afraid of her going into the public school system? Absolutely,” Mendo said of her daughter. “I want her to have as normal a life as possible.”

Researchers studying the long-term effects of gun violence in schools have quantified the protracted struggles among survivors, including long-term academic impacts such as absenteeism, reduced college enrollment and lower earnings later in life.

“Just counting deaths is the wrong way to measure the full cost of these tragedies,” said Maya Rosin-Slater, an associate professor in the Department of Health Policy at Stanford University School of Medicine.

Mass killings have occurred frequently since Columbine, with nearly 600 attacks killing four or more people since 2006, not including the perpetrators, according to data compiled by The Associated Press.

More than 80 percent of the 3,045 victims of these attacks were shot.

Rosin-Slater said hundreds of thousands of people across the country have experienced school shootings, which are typically not mass casualty incidents but are still traumatic. The effects can last a lifetime, leading to “some degree of ongoing, reduced potential” in survivors, she added.

Those who attended Columbine say they have had time in the years since to learn more about what happened to them and how to cope.

Heather Martin, 42, was a senior at Columbine in 1999. In college, she started crying during a fire drill and later realized that fire alarms had been going off for three hours while she and 60 other students holed up in a barricaded office during high school. School shootings. She was unable to return to that class and was marked absent each time, she said, and despite telling professors about her experience at Columbine, her refusal to write a final paper on campus violence led to her failed the exam.

It took her 10 years to see herself as a survivor after she was invited to attend an anniversary event with other classmates in 1999. She saw her classmates having similar struggles and almost immediately decided to go back to college to become a teacher.

Martin, one of the co-founders of The Rebels Project (named after the Columbine mascot), said 25 years has given her time to struggle and figure out how to get out of these troubles.

“I know myself well now, how I respond to things, what might activate me, and how I can bounce back. Most importantly, I think I can recognize when I’m not feeling well and when I really need to ask for help. ,”she says.

Kiki Leyba was a first-year teacher at Columbine University in 1999, shortly after the shooting when she was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. He felt a strong sense of mission to return to school and immerse himself in his work. But he continued to have panic attacks.

Leba said that to help him cope with his anxiety, he takes sleeping pills and some anti-anxiety medications. One therapist recommended chamomile tea.

His situation became even more difficult after the 2002 graduation of Mendo’s class, one of the last students to experience the shooting because they had been through so much together.

By 2005, after years of being unable to care for himself and sleep-deprived, Leba said he was often withdrawing from family life, sleeping in on weekends and becoming “a ball on the couch.” Eventually, his wife, Kelly, signed him up for a week-long trauma treatment program and arranged for him to take time off without notifying him.

“Thankfully, it really gave me a footing … to be able to get out of my shell,” Leba said. Breathing exercises, journaling, meditation and antidepressant medication all helped, he said.

Like Mendo and Martin, he has traveled across the country working with survivors of shootings.

“The worst day has turned into something I can offer others,” Leba said. He is in Washington, D.C., this week meeting with officials to discuss gun violence and promote a new film about his traumatic experience.

Mendo still lives in the area and her 5-year-old daughter attends school near Columbine. Last year, when her daughter’s school was on lockdown as police swarmed during a hostage situation, Mendo recalled worrying things like: What if my child is in danger? What if there was another school shooting like Columbine?

When Mendo picked up her daughter, she looked a little scared and hugged her mother tighter. Mendo took deep breaths to stay calm, a technique she learned in therapy, and put on a brave face.

“If I let go of some fear, she picks it up,” she said. “I don’t want her to do this.”

Follow us on Google news ,Twitter , and Join Whatsapp Group of thelocalreport.in