The National Archives in Seattle holds 50,000 records from the Chinese Exclusion Act era, which prohibited Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States. Volunteers sorting through the documents discovered stories of resilience and, in some cases, details about their families’ pasts.

A group of volunteers gathers at the Seattle Archives every week to index thousands of documents from the period when the Chinese Exclusion Act was in effect. Volunteers say they never know what drama the archives will reveal. It could be an intrusive inquiry about a woman’s pregnancy or a letter from a husband to the detention center authorities requesting to transfer money to his wife.

“No, they weren’t happy, but at least there was the story,” said genealogist and historian Trish Hackett Nicola.She has been volunteering National Archives Project Over 20 years, some of the stories have been shared on the project’s blog.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 suspended the immigration of Chinese laborers to the United States and prevented those already in the United States from becoming naturalized citizens. The act was repealed in 1943. The National Archives in Seattle holds more than 50,000 files spanning more than 60 years, documenting the movement of Chinese in and out of the country.

“Immigration was interrogated, and that clearly changed during the exclusion period,” said Valerie Szwaya, director of archival operations at the National Archives in Seattle. “They become more detailed as the exclusion period goes on.”

Volunteer Rhonda Farrar joined the project to solve the mystery of her family’s past. As she worked on the files, she said, she found that sometimes the problems were annoying and sometimes mundane.

“They’ll ask you how many mirrors you have in your home in China, where you sleep, and where you put the rice,” Farrar said.

Sometimes, they’re about family.

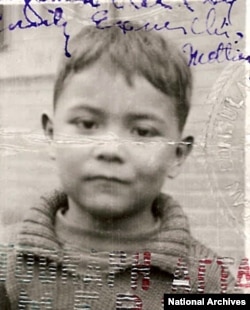

Farrar’s father, Edwin Law, died when she was a teenager. As she was working through files from the Act’s final years, she discovered a file on him. The document misspelled his name as “Low Yow Edwin.” He was interrogated at the start of World War II when he left the United States to serve as a fighter pilot mechanic in the Chinese army. I was stunned to find his papers.

“My job that day was just to check the files and enter the names I saw on the titles into the computer,” she said. “This file is at the very end of this box. I thought, ‘This looks a little like my father’s name.’ ” I opened it and there was a picture of him at 23 years old, staring me in the face. My body started shaking and I burst into tears, it was unbelievable. It really helped me to make everything It’s all integrated.”

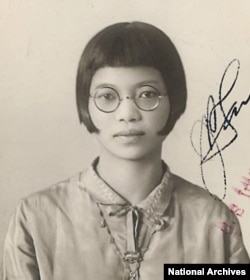

Lily Ying found the files of several family members, including her great-grandfather, who went by the name “Hop Lee.”

“We have no pictures; my grandfather never talked about him,” Eng said. “It wasn’t until I got the immigration files that I realized my great-grandfather had died in 1918, so my grandfather had never met him. His father had returned to the United States before my grandfather was born.”

Joyce Liu, who joined the project as a volunteer a year ago, said the stories revealed through the archives gave her an appreciation for the resilience of the early Chinese people who came to the United States.

“I looked at their lives and it looked very difficult,” she said. “A mother who came back from China with her son had an entry form that said her son died on the ship… I was shocked. I mean, the mother must be devastated. It also dawned on me that the voyage from South China to Seattle required for how long?”

Liu viewed the Chinese who arrived in the United States during the Chinese Exclusion Act as pioneers.

“History really helps us as a Chinese American put things into perspective, I just hope history doesn’t repeat itself,” she said.

Follow us on Google news ,Twitter , and Join Whatsapp Group of thelocalreport.in