For decades, small grooves on the ancient human teeth were considered to be a proof of the use of equipment – people clean their teeth with sticks or fiber, or reduce gum pain with “toothpicks”.

Some researchers also called it the oldest human habit.

But published in our new conclusions American Journal of Biological AnthropologyChallenging this long -held idea Human development,

We found that these grooves also appear naturally wild PrimatesWith a little support to choose teeth as the reason.

More striking than this, in more than 500 wild primates, 27 species living in both and FossilWe did not find any mark of a common modern dental disease: deep, V-shaped gumline knots called abscess wounds.

Together, it can help reopen these findings how we explain fossil records and raise new questions about specific human methods that our teeth today affect.

Why teeth matters in human development

Teeth are the most durable part of the skeleton and often survive for a long time after the rest of the body decays. Humanists rely on them for ancient diet, lifestyle and reconstruction of health.

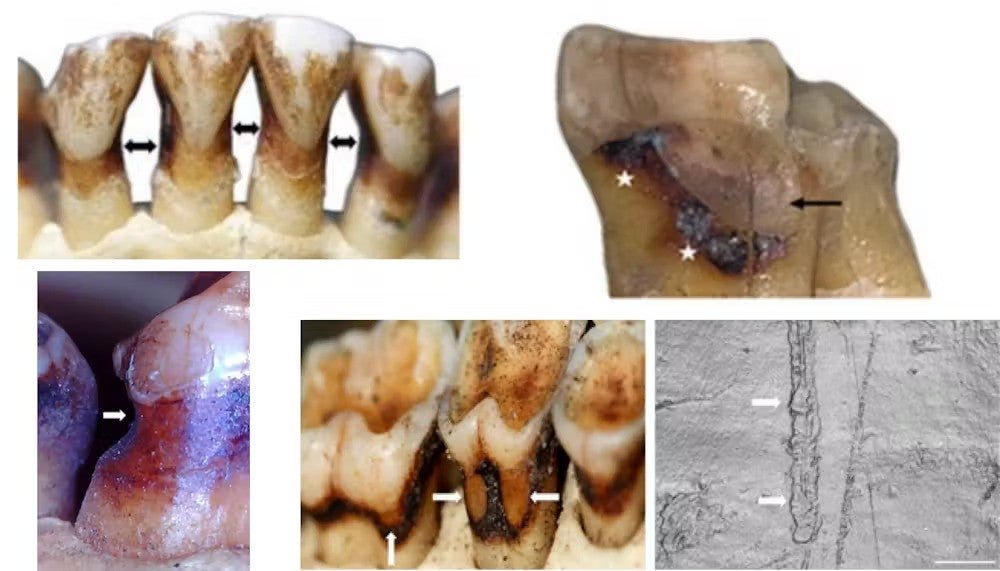

Even small scars can take important meanings. A recurring characteristic is a thin drain between the teeth, especially between the teeth. Since the beginning of the 20th century, they have been labeled “toothpick grooves” and have been interpreted as signs of tools or dental hygiene.

They have been informed through 2 million-year-old fossils to Nendarthal in our recent evolutionary history. But till now, no one had actually investigated whether other primates also have them.

A different position, abfraction, looks very different-dark veg-shaped notch near the gratitude. They are very common in modern dentistry and are often associated with teeth grinding, tremendous brushing, or acidic drinks. The fossil records are long -surprised researchers in his absence. Do other primates never suffer from them?

what we did

To test these beliefs, we analyzed more than 500 teeth from 27 primate species, both extinct and alive. The sample included gorillas, oranges, makak, colobus monkeys, fossil apes and more.

Seriously, all samples came from the wild population, meaning that wearing their teeth could not affect toothbrushes, soft drinks or processed foods.

We did not search for non-cervical wounds-not a name for loss of tissue on the neck of the tissues. Using microscope, 3D scan and tissue-loss measurement, we also documented the smallest lesions.

what have we got

About 4 percent of individuals had wounds. Some people looked similar to the classic “toothpick grooves” of fossil humans, which are completed with proper parallel scratches and taping shapes.

Others were shallow and smooth, especially on the front teeth, due to acidic fruits, many primets consume large amounts.

But an absence stood out. We did not get any abscess wound. Despite studying species with extremely difficult diet and powerful chewing forces, a single primate did not show the shape of a wedge commonly seen in modern dental clinics.

About the author

Ian Tawle is a research partner in biological anthropology at the University of Mamat.

Luka Firanza is a senior lecturer in Physical Sciences at the University of Mamat.

This article was first published Conversation And a creative Commons has been reinstated under the license. read the Original article,

What does this mean?

First, grooves that meet “toothpick” marks do not prove the required equipment. Natural chewing, abrasive foods, or even swallowing grits can produce similar patterns. In some cases, special behavior such as snatching vegetation along the teeth can also contribute. Therefore, we need to be cautious about interpreting every fossil drain intentionally as toothpings.

Second, complete absence of abscess wounds in primates strongly suggest that these are a specific human problem, bound by modern habits. They are more likely due to powerful brushing, acidic drinks and processed diets than natural chewing forces.

It along with other dental issues -along with the affected knowledge teeth and wrong teeth, which are rare in wild primates, but are common in humans today. Together, this insight is shaping a growing subfield known as evolutionary dentistry, using our evolutionary past to understand the dental problems of the present.

Why does it matter today

At first glance, the grooves on the fossil teeth may look trivial. But they matter to both anthropology and dentistry.

For evolutionary science, they show why we should examine our close relatives before taking a specific, or unique, cultural explanation. For modern health, they throw light on how our diet and lifestyle change our teeth in ways that distinguish us from other primates.

By comparing human teeth with other primates, we can separate that universal (unavoidable wear and chewing tears) and what is specific humans – the result of modern diet, behavior and dental care.

What will happen next?

Future research will expand into large primet samples, check the dietary link in the wild, and apply advanced imaging to see how the wounds are formed. The purpose of this is how to explain the past by finding new ways about how to prevent dental disease.

What can look like a fossil human tooth-skin drain can just be easily everyday chewing product. Equally, it can reflect other cultural or dietary behaviors that leave the same scars. To uncontrollad these possibilities, we need a very large comparative dataset of lesions in wild primets, only then we can begin to detect wider patterns and refine our interpretations of fossil records.

Meanwhile, the absence of lesions in primates suggest that some of our most common dental problems are typical human. It is a reminder that everyday in the form of toothache, our evolutionary history is written in our teeth, but is shaped by modern habits by ancient biology.